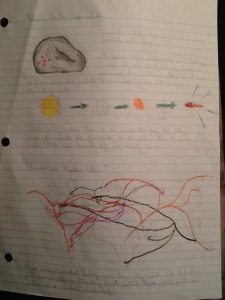

The nature walk we took the other day in class helped me realize the importance of creating nature appreciation in the journey towards ecoliteracy. During the walk, some lichen on a rock caught my attention. I had learned at some point in Bio 101 the symbiotic nature of lichen but it was a fact since forgotten. Now I have an experiential memory with which to associate lichen and will most likely now be able to remember the symbiotic nature between the cyanobacteria and fungus. Recognition of this symbiosis inspired a flow diagram from the sun to the eventual soil creation from the break down of the rock. From the soil, the branching can really start to spread reinforcing the notion of the interconnectedness of nature.

The second drawing is a very limited flow map of some of the human migrations I could think of over the past 40,000 years. The map became unreadable pretty quickly due to the sheer volume of migrations. What it shows to me is the human race is dynamic and ultimately is not fixed to any geographical location. If one looks closely at the flow map, one can find the colonial period in which two opposite moving migratory paths finally crashed into each other (and boy did they ever). In “Canoe Pedagogy”, Liz Newberry (2012) chooses to make this period the focal point in which to understand the world today. It’s a good period to investigate considering it leads to our current political and power dynamics. Further, only in examining the history of colonialism can one understand the development of the structural poverty and marginalization faced by indigenous peoples (though this knowledge should not be what compels one towards social justice but rather compassion for your fellow man should be the driving engine, not ‘liberal guilt’). But one could argue in the macro scale in the distant future, the colonial era will eventually be viewed as just another major human migration; done by humanity many times before where populations mix and displace each other.

As for Newberry’s (2012) application of colonial history towards nature she states, “Because wilderness is dependent on the displacement of Aboriginal people, canoe-tripping in wilderness spaces is not and can never be innocent or uncomplicated.” I understand the sentiment; all which we enjoy in North America (our wealth, nature, etc.) is predicated on aboriginal displacement (a position we may find a lot of people display apathy or even tacit acceptance), but it portrays aboriginals as static, forever tied to the land, and constructs Europeans as somehow distinct from the human migratory experience. Populations have moved, displaced and mixed with each other for millennia. If we want to really construct the stories of our landscapes, we cannot think only in terms of pre and post European contact.

References

Newberry, L. (2012). Canoe Pedagogy and Colonial History: Exploring contested spaces of outdoor environmental education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education. 17, 30-45.

Carter I like how you connected the idea of colonialism to the learning we did on our nature walk. It’s good that you were able to make the connection about how it is important to link our nature side to our educational side to become more ecoliterate. I would like to know more about your opinion on teaching colonialism however. What is your opinion on the way we approach it in our school system.

LikeLike